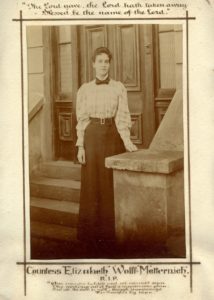

Countess Elizabeth Wolff-Metternich

The Loreto Sisters were invited to Ballarat by the first Bishop, Dr Michael O’Connor, led by Mother Gonzaga Barry (a group of eight Sisters plus two postulants travelled to Ballarat). Mother Gonzaga went on with her work to open a boarding school for girls here at Mary’s Mount (now called Loreto College) and shortly after a day school in Dawson Street.

Gonzaga had many dreams for her schools. One was to build a Church, as worthy as possible to be the house of the Lord, “beautiful so as to lift the hearts of those who entered it to God”. On her journeys overseas she saw many beautiful churches and noted the features she would like in the “Children’s Church” (as she called it); such as the star-studded ceiling which she saw in the Church, Ara Coeli, in Rome, however, she had very little money.

Mother Gonzaga encouraged the children to bring donations. Their donations were recorded in a big red book which was placed in the front hall. She wanted the Church to be built with contributions which came through the children’s hands, hence the name the “Children’s Church”.

Mother Gonzaga encouraged the children to bring donations. Their donations were recorded in a big red book which was placed in the front hall. She wanted the Church to be built with contributions which came through the children’s hands, hence the name the “Children’s Church”.

At long last, she was able to take the plans (made by Mr William Tappin, Ballarat, Architect) to the Bishop, Dr Moore and on 8 January, 1898 Bishop Moore laid the foundation stone of the Church. However, the money ran out only a few months later when the walls were only about 2 ft high because the foundations had to be unusually deep owing to the nature of the soil.

In Autumn that year, a young lady appeared at the convent door. She gave her name as “Miss Metternich”. She came from Germany and was accompanied by her chaperone, Miss Ryan. Miss Metternich had come to Ballarat because she wanted to visit a mining city – she even purchased a miner’s right and spade! She had a dear young friend in Germany who had been a pupil at Loreto Abbey, Rathfarnham, Ireland and always spoke in glowing terms of the nuns. When Miss Metternich heard that the Loreto Nuns were in Ballarat, she wanted to meet them. She requested to board and study for Matriculation. The Superior told her that Reverend Mother had an objection to accepting students for Matriculation, who were too old to follow the school routine. However, she would ask Reverend Mother, and Miss Metternich would receive her answer the next morning.

The next day they returned and Reverend Mother was charmed with Miss Metternich, such a beautiful, simple, refined girl. Mother Gonzaga was impressed that these two ladies were anxious to matriculate in order to secure a higher salary in a situation, so she agreed to their coming, even suggesting delicately that Miss Metternich could perhaps conduct a class in German and that would be counted as part-payment of her pension (fees). Miss Metternich smiled and said she had never done so, by would try. The young ladies were taken on a tour of the convent and then Mother Gonzaga provided lunch for the “poor foreigners” (the Countess said later that she was starving and very grateful).

A few weeks later Miss Metternich arrived with her luggage and was welcomed by Mother Aloysius, the Superior, to whom Miss Metternich confessed that she was the Countess Elizabeth Wolff Metternich, but she wanted it kept secret as she disliked publicity. She said, “I can’t help being a Countess, and when people discover who I am, they either make too much of me or drop away from me”. It did not stay a secret for long!

The Countess also told the nuns that she was a direct descendant of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (daughter of Andrew II, King of Hungary, born 1207). Later Miss Ryan joined her and later still her maid, Katarina, was sent for (she had been staying at a Melbourne Convent of the Good Shepherd).

Countess Elizabeth (the children called her Lady Elizabeth) worked energetically at her studies, but the nuns had to limit her subjects and shorten her hours of study out of concern for her health which was frail. She loved music, played piano, harp and violin, and she gave some help to a class in German. She was very devout, attended daily Mass, became a Child of Mary, and wore the “Broad Blue” ribbon and medal, as the girls did. She took part in many of the school celebrations and activities. One of these was a set of tableaux depicting scenes from the life of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary. The Countess took the role of the Saint, with her beautiful long hair flowing loose (see photographs, E.B. 1898).

The Countess soon expressed a desire to enter the convent here. The novice Mistress, Mother Stanislaus, said she would love to have her in the Novitiate, but told Elizabeth she would need to get stronger health-wise – perhaps she needed to wait another two years. Elizabeth did not want to wait that long.

While she was away travelling, her younger brother died, and her uncle, the executor of her father’s Will, wanted all the family together to settle their affairs. Elizabeth did not want to go home to Germany. The Countess said she would agree to any arrangement the family made, but she did not want to return to Germany. However, yielding to Mother Gonzaga’s persuasion, she eventually agreed to go, but she would not leave till March and would return in November. She wept saying that something was telling her that she would never see the nuns again.

While she was away travelling, her younger brother died, and her uncle, the executor of her father’s Will, wanted all the family together to settle their affairs. Elizabeth did not want to go home to Germany. The Countess said she would agree to any arrangement the family made, but she did not want to return to Germany. However, yielding to Mother Gonzaga’s persuasion, she eventually agreed to go, but she would not leave till March and would return in November. She wept saying that something was telling her that she would never see the nuns again.

Elizabeth was very interested in the Church that Mother Gonzaga was hoping to complete. She offered to give the altar or the organ for the Church as a memorial of her visit to the Abbey. Before she left she made her Will and departed on 16 March, 1899. A bright loving letter came from her during the voyage. The last one from Ceylon said, “only seven months till I see you again!”

Then suddenly a telegram arrived announcing the Countess' death on 28 April, 1899. Two days before the steamer arrived at Marseilles she was at a ball on the ship when she received word that a frail boy in the steerage had suddenly taken ill. The Countess frequently visited the poorer travellers in steerage and she had taken a particular interest in this child and his mother. Without wrapping up against the cold, she went to them and spent some time helping to nurse the boy.

Then suddenly a telegram arrived announcing the Countess' death on 28 April, 1899. Two days before the steamer arrived at Marseilles she was at a ball on the ship when she received word that a frail boy in the steerage had suddenly taken ill. The Countess frequently visited the poorer travellers in steerage and she had taken a particular interest in this child and his mother. Without wrapping up against the cold, she went to them and spent some time helping to nurse the boy.

Shortly after caring for the boy, The Countess, who had already had a haemorrhage during the voyage, began to haemorrhage again, then pneumonia set in and she died. Her body was taken on to Marseilles and then by rail to Cologne, to be laid in the family vault. According to a note from Miss Ryan, her chaperone, to the nuns, almost the last words of the Countess were “Reverend Mother shall have her chapel”. When the Countess’ Will was read she had left more than £15,000 to Reverend Mother Gonzaga to be used as she wished.

The Metternich family were prompt in telling Mother Gonzaga that the Will would be carried out as soon as possible and were always most generous and courteous towards her. In spite of their efforts the money did not come until November 1901, by which time the building of the Church had started again in September 1899 and stopped again in August 1900. The Chapel was ultimately completed due to the foresight, spirit and generosity of the Countess.

More information

View and download more information below regarding the fascinating life of Countess Elizabeth Wolff Metternich and her generosity that resulted in the completion of The Chapel.